Empathy is a buzzword in the tech industry. Although it’s important to work to understand the needs of the humans using our products, sometimes it seems like we talk about empathy more than we actually do it.

"Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another."

Silicon Valley is a notoriously insular place to work. During the two years I commuted from San Francisco to the peninsula, I spent the vast majority of my time with people who were a lot like me. It was easy to forget that the experience I lived every day wasn’t representative of the vast majority of humans my products were trying to serve.

Platitudes about empathy are thrown around like confetti in meetings and conferences. I’ve done this myself without seriously considering what it means to make empathy a guiding principle in how we conceive of, plan and build products. Even if intentions are good (and they usually are), when the tech industry co-opts a concept or term, it can feel a bit like we’re a bunch of robots trying to act out human feelings.

Have a look at some of these headlines (some of the articles are more nuanced than the headlines imply):

- Emulating Empathy

- Why every tech company needs to integrate empathy

- Facebook adds “empathy” reactions

- Empathy Machine

When tech people casually reference empathy they’re treating it like just another commodity. This isn’t intentional or malicious. It’s a by-product of living in a world of ultimate convenience and privilege. But you can’t order up empathy the way you can order a ride or dinner.

Empathy takes practice.

"You can’t order up empathy the way you can order a ride or dinner. Empathy takes practice."

Doing Empathy

Practice: Perform (an activity) or exercise (a skill) repeatedly or regularly in order to improve or maintain one’s proficiency.

There are a thousand big and small ways to practice empathy as part of a product design and development process. But it’s hard because it means you need to change the way you work.

Here are some ideas:

Seek regular feedback from people who aren’t like you

Building an understanding about the people who use your product is a process of continual improvement. Ideally, it means meeting people where they’re comfortable, listening to what they have to say, and doing this all on a regular basis (yes, even when you’re very, very busy). For this to matter you need to be willing to make real changes to your product as you begin to understand:

- What they care about

- What their pain points are

- How you are uniquely positioned to respond to their needs

As a writer, I pay particular attention to the language people use and the comparisons and examples they lean on to make sense of things.

This isn’t an opportunity to sell, pitch, justify or provide corrections. Be quiet, be open-minded and listen.

"Building an understanding about the people who use your product is a process of continual improvement."

Map out tasks

When you’re designing a new product or feature, it’s easy to get caught up in the excitement and potential of what’s possible. But what’s possible isn’t always what’s needed or what’s appropriate. Just because you can do something innovative, doesn’t always mean you should.

In UX Matters, Steve Hoober defines the process of task mapping as “a diagram that describes the entire scope of the system from the point of view of the user— considering all touchpoint, all actors, and all storage and delays.” A task map isn’t a series of screen shots, but a way to represent all the steps in any given task so that you can identify opportunities and pain points. You don’t need fancy software to create a task map. Pen and paper works just fine or you can use any number of mind mapping tools available online.

Task mapping is a great way to examine and evaluate your product so that you can identify opportunities to clarify and simplify experiences to make it easier for people to do the things that matter to them.

Understand and re-evaluate key metrics

Most companies pay attention to certain metrics as a way to make sure they’re meeting business objectives and spending resources wisely. Key metrics are also used to motivate teams to meet specific goals.

"The problem with being too focused on quantitative metrics is that they usually only tell one part of the story"

The problem with being too focused on quantitative metrics is that they usually only tell one part of the story and they’re easy to manipulate. For example, if email clickthroughs are my key metric and my bonus is based on increasing clickthroughs, I can do all kinds of things to inflate my numbers, none of which are a good experience for users. I could:

- Use clickbait link text to wrongly imply that people will see something important or special if they click

- Design bigger, brighter, animated buttons with larger click targets

- Imply a false sense of urgency or scarcity that all but forces people to click

- Provide only teaser information in my email so that people need to click through to see the meat of the content (ex: someone did something that impacts you, click to see)

Doing any of these things might increase the clickthrough rate in emails and from that perspective, I’ve succeeded and deserve my reward. But none of these tactics are good for the people receiving my emails and in the long run, they’re bad for my company. People will only put up with manipulation and spam for so long before they unsubscribe or stop using a product entirely.

"You can practice empathy and work towards achieving quantitative goals"

You can practice empathy and work towards achieving quantitative goals but it requires a nuanced conversation and planning. You need to be able to honestly answer questions like these:

- What is the ultimate company goal that’s informing how and what you measure?

- Is your key metric the right way to measure progress against company goals?

- Are there other more user-centered opportunities for achieving the company goals that your team hasn’t considered?

- What does your key metric represent in human terms? (ex: clickthroughs isn’t a very human way to characterize an experience you’re building for people)

- How will you factor in qualitative feedback and evaluation to measure if your tactics impact user sentiment?

If my key metric is to increase clicks on emails, the conversation I need to have with myself and my team should be:

- Do our email provide any/enough value for our customers?

- How can we increase the value of our emails for customers?

- What do our customers need from our emails? What do they want from our emails?

- What can we offer our customers on our website to justify their click?

Practicing empathy means it will probably take longer to achieve your targets because you have to work harder and be more customer-focused to get there. It also might mean that you need to have a hard conversation with your company leaders about whether achieving the numbers they care about can be accomplished without jeopardizing your ability to do right by your users.

"The language in your product matters as much as the fancy animations..."

Write like a human

The language in your product matters as much as the fancy animations and transitions, the color palettes, or the alignment of buttons. When you’re writing product content, imagine you’re writing for someone you love and choose your words with care. This means:

- Write simply with the goal of communicating clearly.

- Avoid language that tries to manipulate people into taking actions they don’t want to take. If you ever find yourself in a position where you’re using trickery to get someone to do something they don’t want to do, stop pretending you care about empathy.

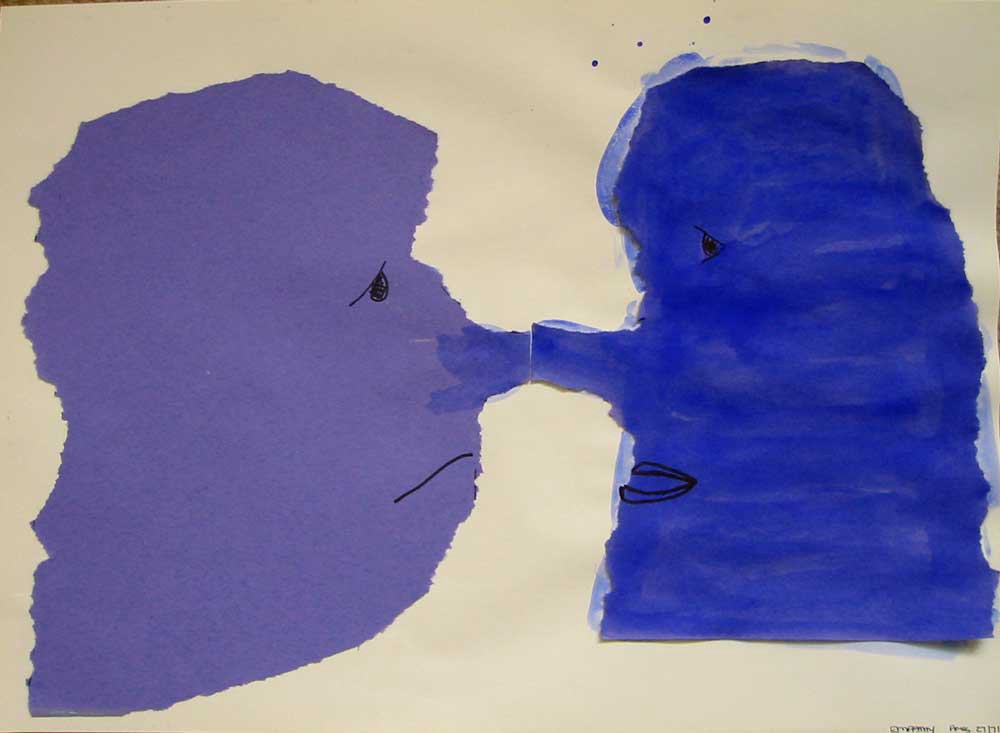

Image Credit: Harper’s Bazaar via The Cruelest Opt Out Forms

- Identify and eliminate internal jargon and ego language. Your customers don’t care where you did your MBA or the big words you know, and they’re not interested in your internal acronyms or code names.

Read your writing out loud, even UX content. Does it sound clear, human and kind? Hey, you’re doing empathy!

Design for real life

Even if you’ve gone to the trouble of developing personas in an attempt to better understand your customers, most people don’t fit neatly into boxes. If you want to practice empathy, you need to be willing to go to dark places and think through the worst possible scenarios. Imagine your users at their most vulnerable and think about your product experience from their perspective. Design for Real Life by Sara Wachter-Boettcher and Eric Meyer is a great place to start if you want to delve deeper into this topic.

"If you want to practice empathy, you need to be willing to go to dark places"

Empathy is a practice. It’s not something you acquire by saying the word. If all of this sounds like a lot of work, that’s because it is. It’s hard to put the experiences and needs of others first especially when we’re stressed out, time constrained, and caught between trying to do what’s best for users and the move-fast, think-later reality of much of the tech world. Even the nicest people struggle to be friendly, generous and considerate all the time. But they keep trying, they course correct, they practice.

Follow Write Like a Human for insights and tactical tips to help you think critically about language and build better products.

This post was originally published on Amy’s Medium profile.